Useful Research on Hidden Biases in the cockpit – TRAINING as the Antidote!!!

A recent, fascinating study in The Applied Cognitive Psychology journal is a useful tool for aviation safety professionals. The well-designed psychological experiment conclusively demonstrates that EVEN commercial pilots with at least 2,000 hours are subject to a cognitive phenomenon known as OUTCOME BIAS.

The study suggests that airline training organizations must incorporate some pedagogical simulation sessions in which the pilot increases his/her tendencies to “do what worked the last time this safety scenario was faced.” A copy of “All’s well that ends well? Outcome bias in pilots during instrument flight rules“ should be included in every recurring class.

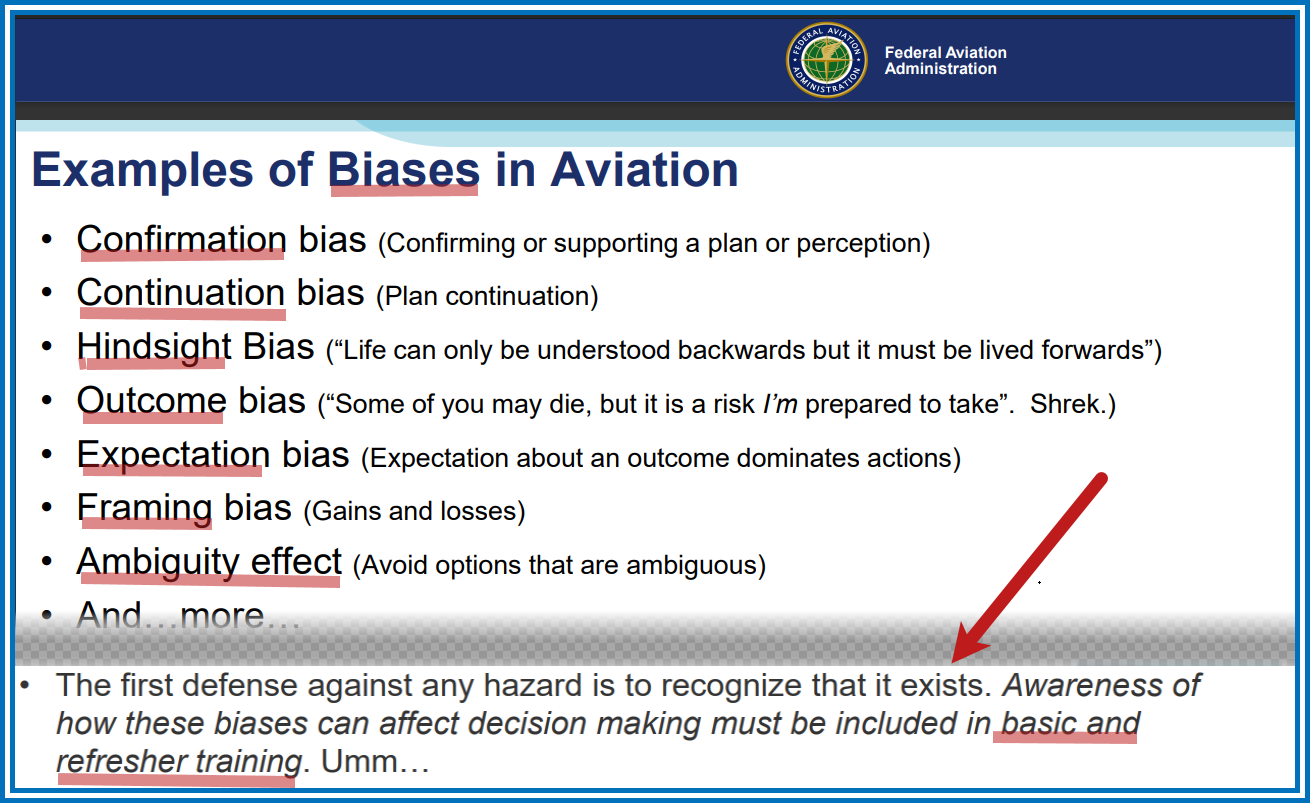

A brief review of available FAA materials show that various biases have been flagged as risks as early as 2012.

What We Hear – Expectation Bias

A pilot calls the tower and reports ready for departure on Runway 10. The controller clears the pilot for takeoff on Runway 17. The pilot reads back his clearance for takeoff on Runway 10 – and then stops on the runway when he spots an aircraft inbound opposite direction for his runway.

The Air Traffic Control System is heavily dependent upon verbal communication to exchange information between controllers and pilots. Hearing what we expect to hear is frequently listed as a causal factor for pilot deviations that occur both on the ground and in the air. In the scenario above – the pilot expected to be cleared for takeoff on Runway 10 – and the controller expected to hear from an aircraft that had been taxied to Runway 17. These professionals were captured by their own expectations.

Eurocontrol defines ATC expectation bias as “Having a strong belief or mindset towards a particular outcome”. A recent analysis of runway incursion data shows that expectation bias is one of the most common causal factors for pilot deviations. Data from the Air Traffic Safety Action Program confirms this fact.

What can you do as a pilot to mitigate expectation bias? Understand that expectation bias often affects the verbal transmission of information. When issued instructions by ATC – focus on listening and repeat to yourself exactly what is said in your head – and then apply that information actively. Does the clearance make sense? If something doesn’t make sense (incorrect call sign, runway assignment, altitude, etc.) – then query the controller about it.

Don’t let your expectations lead to a pilot deviation. Listen carefully – and fly safe!

Another FAA presentation listed seven similar tricks that the brain may play on the cockpit team. These influences are largely subconscious and thus may effect flying without recognition of even the most seasoned ATP. This guidance also emphasizes the need to incorporate training to increase PICs’ and SICs’ awareness.

Pia Bergqvist of Flying magazine has published a very instructive article, Expectation Bias Can Cause Incidents—or Worse.

SkyLibrary created a compendium of relevant advice in a site entitled Hindsight and Outcome Bias

Human memory exerts tremendous power over human behaviour and does not display its influence on our consciousness. It is strong enough to override years of training. The only way to try to counteract this imperceptible aspect of pilots’ actions is TO RAISE AWARENESS.

Even seasoned pilots fall prey to outcome bias, study in Applied Cognitive Psychology reveals

in Aviation Psychology and Human Factors

(Photo credit: Adobe Stock)

In a fascinating exploration into the minds of pilots, a recent study has unearthed that the OUTCOMES OF PAST DECISIONS, WHETHER GOOD OR BAD, SIGNIFICANTLY SWAY HOW PILOTS EVALUATE THE QUALITY OF THOSE DECISIONS. This phenomenon, known as OUTCOME BIAS, was observed across various simulated flight scenarios, revealing that even experienced pilots are more likely to judge a decision negatively if it leads to a poor result, regardless of the decision-making process itself.

The findings, published in Applied Cognitive Psychology, underscore the complex nature of human judgment and highlight the need for aviation training programs to address cognitive biases more thoroughly.

Why embark on this study? The motivation is rooted in the critical nature of aviation decisions. While pilots often rely on standardized procedures, checklists, and operating manuals for decision-making, they also face scenarios that demand RAPID JUDGMENT CALLS in the absence of complete information and under the PRESSURE OF SEVERAL COMPETING ALTERNATIVES. This type of decision-making is inherently more complex and fraught with the potential for error.

Previous research has highlighted that a significant portion of aviation accidents are due to human error, with a CONSIDERABLE NUMBER of these errors tied to DECISION-MAKING UNDER PRESSURE. Given these stakes, the researchers aimed to delve deeper into the cognitive processes underpinning pilot decision-making, particularly the role of OUTCOME BIAS — a psychological phenomenon where the results of a decision influence how we view the quality of that decision in hindsight.

The researchers recruited 60 pilots who were qualified to fly under instrument flight rules (IFR), dividing them into two categories based on their experience. Expertise was determined by the number of hours each pilot had logged as pilot-in-command (PIC), with those accumulating more than 2,000 hours classified as experts, and those with fewer as novices.

Participants were presented with four carefully crafted scenarios through an online survey. These scenarios simulated real-world decisions pilots might face while flying under IFR. The scenarios were developed with input from seasoned pilots to ensure realism and relevance. Each scenario concluded with either a positive or negative outcome, designed to test the impact of outcome knowledge on the pilots’ evaluations.

The scenarios were as follows:

- A flight with minimum fuel expecting clear weather, which either lands safely or requires a go-around due to unanticipated bad weather.

- A decision to fly above clouds to save fuel, leading either to an uneventful flight or ice crystal icing causing technical issues.

- Continuing an approach despite a red cell (heavy rain) on the weather radar, which ends either with a safe landing or a downdraft necessitating a windshear escape maneuver.

- Landing in freezing rain with no reported braking action value, resulting in either a safe stop or an overshoot of the runway.

Participants rated each scenario on three aspects: the DECISION’S QUALITY, the PERCEIVED RISK, and THEIR LIKELIHOOD OF MAKING THE SAME DECISION.

The study’s findings revealed a significant presence of outcome bias across all measures. Decisions that led to positive outcomes were rated more favorably in terms of decision quality, perceived risk, and the likelihood of making the same choice, compared to those with negative outcomes. This trend persisted regardless of the pilots’ experience, indicating that both novices and experts were equally influenced by the outcomes when evaluating past decisions.

These findings underscore the SIGNIFICANT ROLE OF OUTCOME BIAS in the decision-making processes of pilots, CHALLENGING THE ASSUMPTION that EXPERIENCE ALONE CAN MITIGATE THE INFLUENCE OF COGNITIVE BIASES.

The study’s insights into how pilots evaluate past decisions based on outcomes rather than the information available at the time have IMPORTANT IMPLICATIONS FOR AVIATION SAFETY AND TRAINING. By recognizing the impact of outcome bias, training programs can be better designed to address these cognitive biases, potentially leading to improved decision-making processes and enhancing overall flight safety.

The findings open up several avenues for future research. There’s a need to explore other cognitive heuristics that pilots may rely on during decision-making and to investigate whether these biases affect judgment in real-life flight situations as strongly as they do in simulated scenarios. Moreover, comparing the decision-making processes in aviation with those in other high-stakes fields, like medicine, could offer deeper insights into how professionals manage risk and uncertainty.

The study, “All’s well that ends well? Outcome bias in pilots during instrument flight rules“, was authored by Ana P. G. Martins, Moritz V. Köbrich, Nils Carstengerdes, and Marcus Biella.