Will the CENTO test flights in CA test federal preemption? Good reminder that even after CERTIFICATION IS CLEAR–THERE’S STILL MAJOR HURDLES

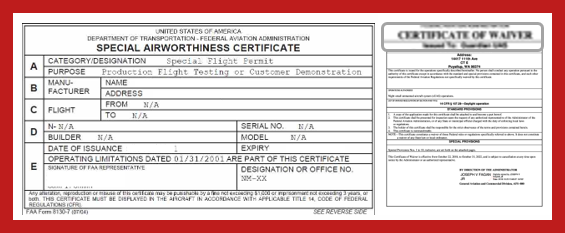

Flying magazine has recently published an extremely informative exposition about MightyPro’s obtaining both an FAA special airworthiness certificate (SAC) and a certificate of waiver or authorization (COA) to test fly its 2024 Cento within a flight corridor between New Jerusalem Airport (1Q4) and Byron Airport (C83) in California. The article describes in detail the operator parameters of this cargo eVTOL aircraft and the potential of this application is impressive. Time spent reading this article would be most worthwhile.

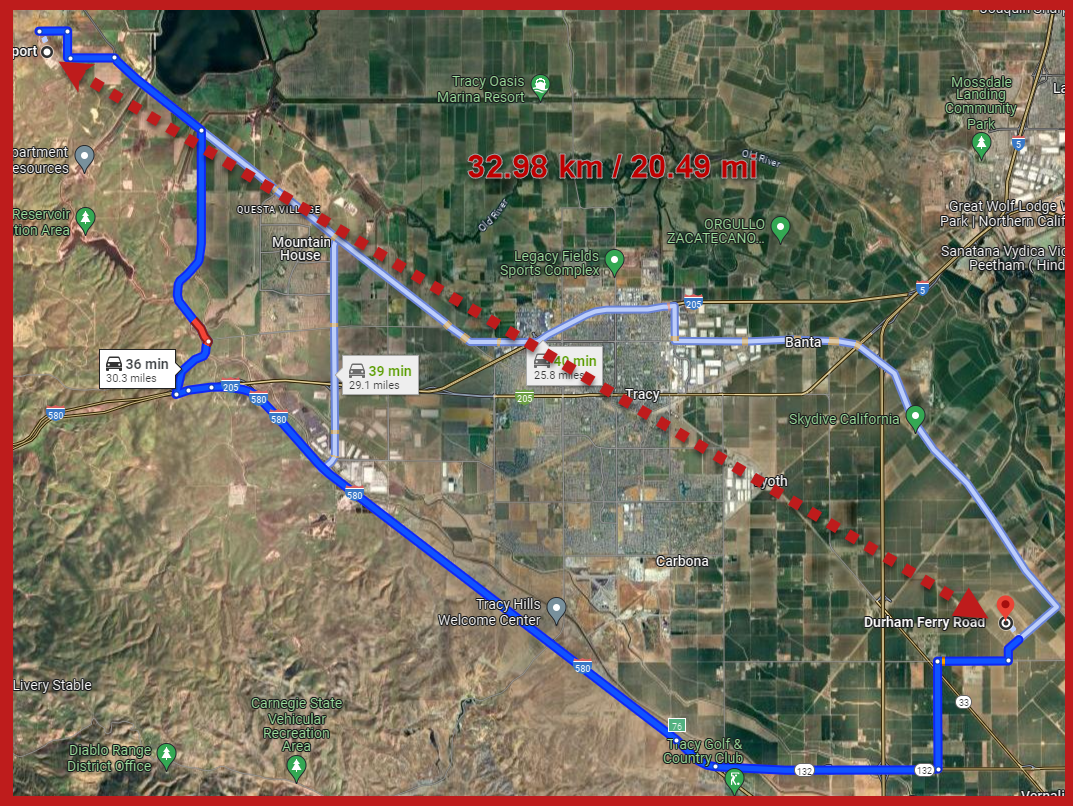

What is not discussed is the local impact. The two airports are in separate California Counties– San Joaquin[1] and Contra Costa. There is no reference about whether the cities or counties intend to impose any limitations on these experimental flights.

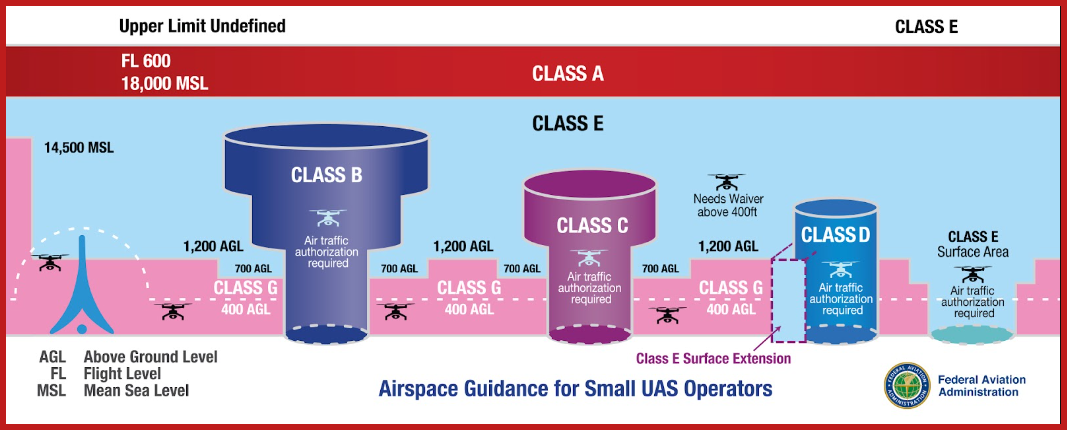

The FAA’s special grant of authority indicates that the CENTO may operate UP to 5,000 AGL. Depending on the time-of-day, altitudes, weather conditions and other factors, the noise impact of these operations may cause local authorities to respond. Such a local attempt to limit eVTOLs might run into one of the law’s most complex legal doctrine—FEDERAL PREEMPTION. In 2023 the DOT/FAA issued State and Local Regulation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Fact Sheet. Suffice it to say that the paper, with obvious parallels to the eVTOL future, is 8 pages of small print, includes the following headings and some substantive subsections:

- “FIELD PREEMPTION – BASIC PRINCIPLES

- CONFLICT PREEMPTION – BASIC PRINCIPLES

- EXPRESS PREEMPTION UNDER THE AIRLINE DEREGULATION ACT OF 1978 – BASIC PRINCIPLES CONCERNING AIR CARRIERS

- EXAMPLES OF STATE AND LOCAL LAWS ADDRESSING UAS THAT WOULD BE SUBJECT TO FEDERAL PREEMPTION

- Regulating UAS operations or restricting flight altitude or flight paths in order to protect the safety of individuals and property on the ground or aircraft passengers, or in order to ensure the efficient use of the airspace by UAS and/or other aircraft;

…

- Designating “highways” or “routes” for UAS;

- Selling or leasing UAS-related air rights above roadways;

- Certain state or local laws aimed at other objectives that impair the reasonable use by UAS of the airspace.

- If a law seeks to advance non-safety or efficiency objectives but affects where UAS may operate in the air, the question of whether the law is preempted will depend primarily on whether the law negatively impacts safety and on how much of an impact the law has on the ability of UAS to use or traverse the airspace.

- EXAMPLES OF STATE AND LOCAL LAWS ADDRESSING UAS THAT WOULD LIKELY NOT BE SUBJECT TO FIELD OR CONFLICT PREEMPTION

- Laws aimed at objectives other than aviation safety or airspace efficiency that do not impair the reasonable use by UAS of the airspace.

- Such laws could include those concerning land use or zoning

- Laws regulating the location of UAS takeoff and landing areas. It is well established that States have a valid interest in choosing where aircraft may operate on the ground. Laws designating takeoff and landing locations have no direct effect on where UAS may operate in the air.

- Laws that prohibit, restrict, or sanction operations by UAS in the immediate reaches of property to the extent that such operations substantially interfere with the property owner’s actual use and enjoyment of the property.

- State and local policies concerning where a UAS operator can be located while conducting operations.

- UAS registration requirements that are ministerial and do not directly or indirectly regulate aviation safety or the efficient use of the airspace.”

As previously mentioned, to parse these “definitive” guidelines in attempting to apply them to these flights requires a first rate Constitutional Scholar. The CENTO flights may be a catalyst to get greater clarity based on specific operations and communities.

One perspective has been fully examined by a Jonathan Dockrell in his Drone Skies Substack Flying Cars website; here are a few subjects on which he has commented:

Utilising Property – Air Rights For Growth

Underutilised Skies And Properties Help Us Fly

Flying Cars – Air Rights In The Driving Seat

Airspace Dynamics, Decentralization and Real Estate Who Has The Rights To Open The Sky

It will be interesting to see if any of these governments attempt to coexist with the evolving eVTOL federal preemption.

++++++++++++++++++++

MightyFly Obtains ‘Industry First’ FAA Flight Corridor Approval in California

The company says its 2024 Cento is the first large, self-flying, electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) cargo drone to receive the consent.

By Jack Daleo

May 3, 2024

A self-flying electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) drone for the cargo logistics industry has obtained a first-of-its-kind approval, according to its manufacturer.

California-based MightyFly this week announced what the company is calling an “industry first” FAA authorization, granting it permission to test its recently unveiled 2024 Cento within a flight corridor between New Jerusalem Airport (1Q4) and Byron Airport (C83) in California.

MightyFly says the approval, obtained in March, is the first for a large, self-flying cargo eVTOL in the U.S. The company in January received an FAA SPECIAL AIRWORTHINESS CERTIFICATE (SAC) AND CERTIFICATE OF WAIVER OR AUTHORIZATION (COA) to establish the corridor.

The firm’s March approval, which it obtained via Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, includes a COA authorizing a flight corridor UP TO 5,000 FEET AGL between New Jerusalem and Byron airports. The COA opens the ability for the company to perform what it terms “A-to-B flights” within the corridor’s general aviation airspace, allowing it to test aircraft range, among other things.

Following ground testing at its headquarters and test site, MightyFly began flying the 2024 Cento at the corridor’s origin airport on March 4. In the span of two months, the company has completed more than 30 autonomous flights, or about one every two days.

Future testing will include A-to-B flights. Eventually, it will expand to additional use cases and markets, MightyFly says.

“This is a solid vote of confidence from the FAA in our work and our ability to perform SAFE AUTONOMOUS FLIGHTS IN THE GENERAL AVIATION AIRSPACE,” said Manal Habib, CEO of MightyFly[2]. “We now look forward to demonstrating point-to-point delivery flights with our partners in this space.”

The authorization also contains a SAC that will allow MightyFly to test Cento’s beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) capabilities, which are considered key for enabling drone delivery at scale.

BVLOS refers to the drone operator’s ability (or lack thereof) to visually monitor the aircraft in the sky. In lieu of a final BVLOS rule, the FAA awards these permissions to select companies via waiver or exemption. But for safety reasons most companies must keep their drones within view of the operator.

However, technologies such as DETECT AND AVOID and REMOTE IDENTIFICATION have the potential to replace human observers as they mature. MightyFly will test Cento’s detect and avoid systems and long-range command and control (C2) datalink communications while the self-flying drone is trailed by a chase airplane.

The SAC also authorizes MightyFly to begin point-to-point autonomous deliveries and proof of concept demonstrations with customers and partners. These will include deliveries of medical and pharmaceutical supplies, spare parts and manufacturing components, and consumer goods within the flight corridor.

Future demonstrations include several planned point-to-point autonomous cargo delivery flights in Michigan under a contract with the state’s Office of Future Mobility and Electrification. The company is also scheduled to demonstrate Cento’s ability to autonomously load, unload, and balance packages for the U.S. Air Force in 2025. These flights, MightyFly says, will mark its “entry into the expedited delivery market.”

The 2024 Cento, MightyFly’s third-generation aircraft, is designed for expedited or “just-in-time” deliveries. Potential customers include manufacturers, medical teams, first responders, retailers, and logistics, automotive, and oil and gas companies.

The third-generation drone is built TO CARRY UP TO 100 POUNDS OF CARGO OVER 600 SM (521 NM), CRUISING AT 150 MPH (130 KNOTS). Under full autonomy, it is expected to be able to land at a fulfillment center, receive packages, fly to a destination, unload its cargo, and take off for its next delivery.

MightyFly’s Autonomous Load Mastering System (ALMS) autonomously opens and closes the cargo bay door, secures packages in (or ejects them from) the cargo hold, and senses the payload’s weight and balance to determine its center of gravity. The company is working with the Air Force and its Air Mobility Command to develop ALMS.

Another key differentiator for the 2024 Cento is its flexibility. The drone can handle a variety of cargo contents, densities, loading orders, and tie-down positions. That means customers won’t need to standardize their packaging or order loading processes to accommodate it. The aircraft can carry refrigeration boxes, for example, which are often used in the healthcare industry to transport organ donations or blood bags.

Jack is a staff writer covering advanced air mobility, including everything from drones to unmanned aircraft systems to space travel—and a whole lot more. He spent close to two years reporting on drone delivery for FreightWaves, covering the biggest news and developments in the space and connecting with industry executives and experts. Jack is also a basketball aficionado, a frequent traveler and a lover of all things logistics.

[1] Lockeford, California, in the same county, was the site for a similar aerial delivery test by Amazon. The operation was terminated and moved to Arizona, The company did not issue a statement about why it was leaving, but a long CBS posting only referenced a resident’s complaint about too many drone flights.

[2] CEO and founder of MightyFly. A graduate from both MIT and Stanford, Habib has developed a strong technical background in aerospace engineering. She previously specialized in flight controls and developed the first robust commercial flight controller. Manal is also a private pilot and in the process of building her own airplane. Her passion for aerospace, vision for a better world, and determination make her a motivated and unstoppable entrepreneur and leader.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++