Secretary and Administrator (D) please make aviation a positive force to quench wildfires ASAP

Apologies to those who regularly read (enjoy?) this blog for being repetitive, but a recent AIN article rekindled the need for highlighting the need for the FAA/DOT to aggressively get involved in this NATIONAL/CONTINENTAL/GLOBAL issue. the recent prognosis for more holocaust-like events is made in the analysis:

“The forecast indicates that significant fire activity continued to increase through August, with the national preparedness level increasing from three to four (scale one to five) on August 17. Significant fire activity increased across most geographic areas in August, including the Southern Area, but decreased in the Southwest Area. A significant rainfall event August 20-23 resulted in decreased activity across the Great Basin, Rocky Mountain, and Northern Rockies Geographic Areas for the end of the month. Alaska continued with elevated activity through mid-month before decreasing rapidly at the end of the month while Hawai’i was very active in August as well, including the Lahaina Fire. Year-to-date acres burned for the US is well below the 10-year average at 38%, with a slightly below average number of fires as well, about 96% of average.”

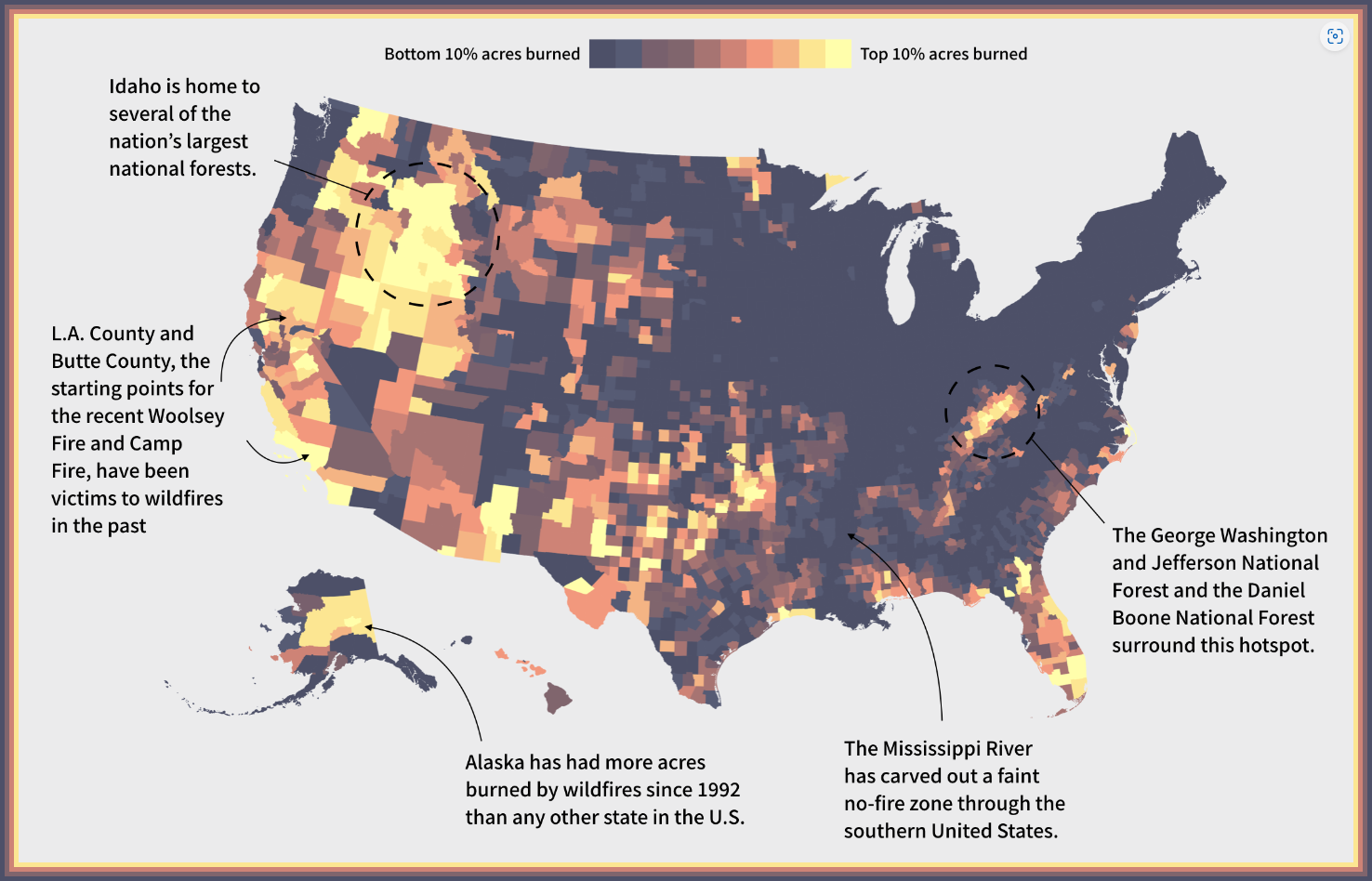

The dimensions of this CRISIS begin on an agricultural/forest management level; accelerate through massive loss of lives, natural resources, wildlife, and what FDR labeled our best idea; but involve climate change as a cause of these conflagrations. As the map suggests, this high profile environmental cataclysm is becoming a national priority.

Aerial firefighting has been highlighted here for years:

- The complex, dynamic and dangerous aerial/ground Firefighting environment [NIOSH] may benefit from SMS-2015

- Aerial Firefighting in US Forests may use Chinese Aircraft in 2015

- New Aerial Firefighting Aircraft come to California, but more safe aerial assets are needed 2019

- 2021 US Aerial Firefighting Capacity under a Level 5 threat

- Aviation’s positive role in the battle to save the planet 2023

The National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) has reiterated the need for aerial vehicles to battle these destructive fires. In January, the Departments of Agriculture, the Interior, and Homeland Security—through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), released the U.S. Forest Service Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission’s Aerial Equipment Strategy Report. That lengthy (52 pages, single spaced, 11 font, no pictures, and few graphs) define the length, breadth and depth of these firestorms. Many strong recommendations are made in the report, which is the work product of 16 federal, 13 NGOs, 10 state, 5 city/county, 4 academics,2 tribal, 0 FAA/DOT MEMBERS!!! Maybe Buttigieg and the parade of Acting FAA Administrators were not invited, but these quotes, copied from the AIN article, suggest NOT:

- “…involves more air attacks on fires, especially when they are in the nascent stages and before they can spread…”

- “But policy roadblocks with regard to restricted category aircraft and how the government employs them—either directly or through contractors—potentially stand in the way…”

- “…A 2017 draft interagency strategy for wildland fire aviation resources has yet to be finalized by the National Interagency Aviation Committee of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group due in part to a LACK OF AVIATION PERFORMANCE DATA.“

- “…A common challenge was the LACK OF INFORMATION ON AIRCRAFT PERFORMANCE AND EFFECTIVENESS, primarily because federal agencies did not collect such data (GAO, 2013). As one example, a 2012 study by the Rand Corporation intended to assess the ideal composition of large aircraft for optimal returns on investment in an initial attack. However, the study’s models produced ‘a frustratingly broad range of answers’ due to what it termed ‘fundamental uncertainties in the science and economics of wildland firefighting’…”

- There’s more… read the original

The lack of information from aviation has been and continues to be a major impediment.

Critique of the DOT/FAA is not limited to the lack of data. The Report castigates the aviation safety regulator in the following paragraph:

Yes, the FAA’s job is SAFETY and protection of the citizens on the ground. That said, regulatory mechanisms can be devised to minimize the gap between filing and authority. Prospective, categorical SRAs can be designed. Regulatory hurdles SHOULD BE LIMITED in cases involving significant loss of life, property, and national treasures. For example, for years the absence of specific protection of infant passengers has been justified by the syllogism that the cost of another seat charge or added restraints would move these customers to riskier transportation modes.

“…That all changed last year when the FAA ENACTED A POLICY, as opposed to a rule, change with regard to J551. Operators now NEEDED TO APPLY FOR A WAIVER FOR EACH FLIGHT 45 DAYS IN ADVANCE and include a RISK ASSESSMENT FOR EACH AIRPORT WHERE A STOP WAS PLANNED…”

If interested in more detail, a good friend of the JDA Journal, Jeffrey Lehman, has co-authored an excellent book, RUNNING OUT OF TIME.

Mr. Secretary Buttigieg and the soon-to-be-Honorable Mr. Whitaker, ADDRESSING THE HELP THAT AERIAL FIREFIGHTING CAN PROVIDE, and eliminating/minimizing regulatory barriers,

MUST BE A PRIORITY!!!

=====================================================================

Burning Questions at the Apex of Fire Fighting Season

U.S. officials are refiguring aerial firefighting requirements

Sikorsky’s Firehawk is a successful fire-suppression aircraft but much more expensive than surplus military Black Hawks. (Photo: Lockheed Martin)

By MARK HUBER

September 1, 2023

By early August, the worst Canadian wildfires on record had torched more than 32 million acres, created the most unhealthy air quality ever measured in several North American cities, and spewed more than 25 percent of the globe’s annual carbon dioxide (CO2) output into the atmosphere. Of the more than 1,000 fires burning, nearly 700 were labeled “OC” or out-of-control, charring an area the size of Greece, from Quebec to well north of the Arctic Circle.

Meanwhile, U.S. POLICYMAKERS ARE GRAPPLING WITH THE NEW REALITY OF FIRE SEASONS THAT ARE LONGER, MORE VOLATILE, AND INCREASINGLY DESTRUCTIVE. And more frequently, the SOLUTION INVOLVES MORE AIR ATTACKS ON FIRES, especially when they are in the nascent stages and before they can spread.

But policy roadblocks with regard to restricted category aircraft and how the government employs them—either directly or through contractors—potentially stand in the way.

According to the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), 31,382 wildfires have burned 1,257,389 acres, well below the 10-year average of 35,011 wildfires and 3,897,571 acres burned at this point in the fire season. But that luck may not hold.

NIFC has warned that dry thunderstorms and hot, dry, and windy conditions have created elevated fire risks in the Western U.S., Texas, the lower Mississippi Valley, and Alaska. Of the more than 500,000 acres ablaze on August 7, only 2,609—in Texas—were classified as “contained” by the NIFC. The clear message: buckle up.

Fighting Wildfires From the Air Now Taken More Seriously

Both the executive branch of government and Congress are taking the growing wildfire threat seriously. In January, the Departments of Agriculture, the Interior, and Homeland Security—through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), released the U.S. Forest Service Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission’s Aerial Equipment Strategy Report.

NOTE: commission members= 16 federal, 13 NGOs, 10 state, 5 city/county, 4 academics,2 tribal, 0 FAA/DOT

The Commission’s interim report—with more findings due out at the end of September—attempted to evaluate structural and policy barriers to effective aerial firefighting, but noted a lack of coherent data on the topic. A 2017 draft interagency strategy for wildland fire aviation resources has yet to be finalized by the National Interagency Aviation Committee of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group due in part to a LACK OF AVIATION PERFORMANCE DATA. A parallel effort, initiated in 2012 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), intended to document aircraft use and effectiveness. In all, that study, published in 2020, took eight years to complete but fell short of comprehensively assessing the performance of all aircraft types and functions during the wildland fire response.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has also been vexed in researching the topic, for largely the same reasons. “A common challenge was the LACK OF INFORMATION ON AIRCRAFT PERFORMANCE AND EFFECTIVENESS, primarily because federal agencies did not collect such data (GAO, 2013). As one example, a 2012 study by the Rand Corporation intended to assess the ideal composition of large aircraft for optimal returns on investment in an initial attack. However, the study’s models produced ‘a frustratingly broad range of answers’ due to what it termed ‘fundamental uncertainties in the science and economics of wildland firefighting’ (Rand Corporation, 2012),” the Forest Service Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission’s report noted, referencing GAO’s conclusions.

It recommended developing national performance measures designed to assist in determining the optimal number of aircraft; cost comparisons between aviation assets owned by the U.S. Department of Defense, government, and the private sector; making national strategy and program needs primary over cost and procurement considerations; increased funding for aviation training and staffing; and exploration of new technology to reduce staffing demands.

Privately-owned firefighting helicopters are typically contracted for by federal and state governments via either “exclusive-use” or “call-when-needed” contracts. Exclusive use contracts provide that the aircraft is available exclusively for a set period of time—generally months—and is the more expensive option versus a call-when-needed arrangement, which is the more popular choice. Industry experts believe only 30 percent of contracts are for exclusive use.

While acknowledging “adoption of military surplus aircraft by either agencies or private contractors carries risks and costs that are often overlooked,” the Commission recognized that “MILITARY SURPLUS PARTS AND EQUIPMENT, including aircraft parts, may be beneficial to state and local wildfire agencies and the private contractor wildfire community.”

Military Helicopters Find Themselves Restricted In Civilian Service

That benefit already is being recognized, with an increasing number of surplus military rotorcraft, particularly Boeing CH-47s and Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawks, finding their way onto the civilian market and being operated under FAA restricted category type certification. An estimated 500 Black Hawks already have been disposed of onto the civil market, with the majority of those being flown in the U.S. Former military aircraft are typically OPERATED IN THE RESTRICTED CATEGORY out of an abundance of caution for public safety, said Brian Beattie, general manager of helicopter operator Croman Corp. and chairman of the aerial firefighting and natural resources working group of Helicopter Association International (HAI).

“When these aircraft got to the end of the production line, they didn’t get an FAA credential, “Beattie noted. A RESTRICTED CERTIFICATE SPELLS OUT WHAT THE AIRCRAFT CAN AND CANNOT DO. CHIEF AMONG THE RESTRICTIONS: THEY CANNOT OPERATE OVER POPULATED AREAS, NEAR BUSY AIRPORTS, OVER CONGESTED AIRWAYS, OR CARRY PASSENGERS. There was a blanket exemption for emergency operations including firefighting and disaster relief, and exceptions to these rules can be made via filling out FAA’s J551 certificate of waiver. For years that process worked fairly well.

Operators could apply for J551s that covered their entire fleets for up to 24 months that were good in all 48 contiguous U.S. states. This made it comparatively easy for operators to move helicopters around in potential service of call-when-needed contracts as these aircraft typically not only handled firefighting but utility missions as well such as long-line logging or construction.

That all changed last year when the FAA ENACTED A POLICY, as opposed to a rule, change with regard to J551. Operators now NEEDED TO APPLY FOR A WAIVER FOR EACH FLIGHT 45 DAYS IN ADVANCE and include a RISK ASSESSMENT FOR EACH AIRPORT WHERE A STOP WAS PLANNED.

“The policy was rewritten because the FAA felt like there were some operators taking advantage of the situation,” surmised Zac Noble, HAI director of flight operations and maintenance. Specifically, rather than overflying a populated area, certain operators were using their J551s to do utility work within an area. So the FAA clamped down on everyone and now “it is very difficult for anyone to get authorization to overfly densely populated areas,” said Noble.

It didn’t take long for the law of unintended consequences to take hold. When Hurricane Ian hit south Florida in 2022, an operator of a civil Black Hawk was denied a J551 trying to deliver meals ready to eat and drinking water to survivors, he said. The HAI and industry have reached out to the FAA in an attempt to get the policy modified. But for now, going into the apex of wildfire season, it remains in place.

New Legislation Is Coming

Congress has addressed the restricted category issue via the proposed FAA reauthorization legislation and aerial firefighting via Interior Department appropriation bills in both the House and Senate. The House already has passed H.R. 3935, “The Securing Growth and Robust Leadership in American Aviation Act,” which, among other things, directs the FAA administrator within 18 months to produce an interim final rule that requires ground firefighters being transported in restricted category aircraft to be categorized as “essential crewmembers” (thus circumventing the restricted category passenger transport ban); places firefighting aircraft maintenance, inspections, and pilot training under Part 135 at the administrator’s discretion; and exempts firefighting aircraft from noise standards.

However, while the legislation proposes to make it easier to carry firefighting crew, it also counterintuitively seeks to restrict the use of former military aircraft for firefighting. According to the act, it provides that the FAA administrator “shall not enable any aircraft of a type that has been manufactured in accordance with the requirements of, and accepted for use by, any branch of the United States military and has been later modified to be used for wildfire suppression operations.”

And that raises the larger question as to why modern aircraft remain subject to what would seem like draconian FAA restrictions once they leave the military. That likely will be the topic of future debate.

“The FAA recognizes that they’re dealing with a rule and a policy that was developed decades and decades ago when

to why modern aircraft remain subject to what would seem like draconian FAA restrictions once they leave the military. That likely will be the topic of future debate.

“The FAA recognizes that they’re dealing with a rule and a policy that was developed decades and decades ago when surplus military aircraft weren’t meant to come back from deployments in Europe or Asia,” Noble said. “That’s where those rules came from. But since 1978 the Black Hawk has accumulated more than ten million safe flight hours. There have only been two civilian crashes to date, but yet we’re still held down by those legacy rules.”

Meanwhile, Canada burns, Washington debates, and the nation waits out another fire season—with fingers crossed.

There is a lot of ignorance about wildland firefighting in that article, starting with reference to “Preparedness Level 3.” This does not mean that the fire service (and various agencies) are unprepared, or even partially prepared. The national preparedness level, as determined by the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), refers to the percentage of resources committed nationally. It does not describe the level of actual “preparedness.” Three means resources are still available.

Changing the restricted airworthiness status of aircraft won’t increase the level of “air attack,” or put more tankers over the fire. Fire resources are requested by incident commanders in real time, and assigned as available. Presently, resources are available. There is a finite pool of qualified operators, pilots and air attack personnel available. I have been over many fires when the public is screaming “more, more,” and yet the airspace was saturated. One can only put so many aircraft into an environment with mountainous terrain severe to extreme turbulence, no radar coverage, low visiblity, and a dynamic, rapidly changing environment.

More aircraft doesn’t mean less fire, nor does it mean more control; aircraft use tactics to modify fire behavior with very specific objectives on very specific parts of a fire, but it’s rare that aircraft are launched to go put a fire out. In many cases, that’s not possible; an active windfire may be releasing more energy than a nuclear weapon, and dropping on it 800-4000 gallons at a time will not extinguish it. What we do is attempt to modify its behavior, and primarily support the objectives of the actual firefighters, who are all on the ground.

Maui was invoked as though it had some relevance to the topic of aircraft over fires. Maui’s recent fires occurred in an environment of high winds when tanker operations and most helicopter bucket operations would have been nearly impossible, and too dangerous. Maui has never conducted tanker operations. It’s in the middle of the pacific, and there are no tankers to send. There was no experience there with tanker operations, nor is there a tanker base in Hawaii. To invoke Maui as having any bearing on air resources over a fire is merely to muddy the waters.

Why did USFS, BLM, BIA, etc, all convene to discuss firefighting, but the FAA did not? Because the FAA isn’t a landholder with responsibilities for wildland fire. The agencies that convened all have an active role in providing firefighters, contracting aircraft and conducting wildland fire operations, where as the FAA does not. The FAA already has oversight of pilot certification, maintenance, etc. The Office of Aircraft Management handles carding of aircraft, operators, pilots, and support equipment, for fires, as well as the National Aerial Firefighting Academy, etc.

Aerial firefighting operations are expensive. Very, very expensive. Cutting corners in the past has proven very costly in terms of lives and operational tempo. Presently the very largest resource available, no longer flies fires; the 747-400 supertanker proved too expensive to contract, and was returned to freight operations

Why are aircraft “subject to draconian restrictions when they leave the military?” They’re not. They don’t have airworthiness certificates. Military aircraft are neither designed nor certificated to civil standards, nor are they maintained with a civil airworthiness program. The fire service has a long history of operating ex military aircraft, and some of the aircraft I have flown over fires have still been in the military inventory. NASA determined that aircraft over fires experience stresses and wear at a rate 500 to 1000 times that of the same aircraft in commercial service; we have seen airplanes shed wings or break up over fires, and presently aircraft are given drastically reduced service lives once they enter the fire service. When the large air tanker program was grounded in 2002, following the inflight breakup of two large air tankers, both aircraft with military history, I was actively flying fires, and had flown both the mishap aircraft, and knew them both very well, as well as the crews. It’s one thing to make a statement in ignorance that the FAA must lift the “draconian restrictions,” but such a statement is made in absence of fact and in ignorance. The present policies exist for a very good reason.

It should be noted that it’s been some years since the USCG released C-130H aircraft for firefighting, only one of which is presently in service, and none of which are in federal service. Two are painted, one is operational. Seven were granted. The transfer process began in 2013, ten years ago, and it will be some time, if ever, that all seven aircraft will be available.

Presently the government does not have the capability to operate an air tanker program, and there is a limited pool of capable operators who can provide fire operations. Even Calfire, which has a long-standing relationship in aerial fire, uses contract services for pilots and maintenance, operating in a “GOCO” (government-owned, contractor-operated) status. Calfire pilots work for Dyn-Corp (now Amentum). Calfire is able to operate aircraft such as the S-2 and OV-10 precisely because of the ability to use them under a restricted category airworthiness certificate: this enables, not restricts the aircraft. The article has it backward.

Aircraft are effective and valued resources on wildland fires, but there are many kinds of aircraft, and the analogy is often given of many tools in the toolbox. Not every tool is appropriate for every fire, and aircraft only assist firefighters; aircraft do not go put fires out. The ideal state is the ability to put a box of retardant around a single tree on a calm day with no other exposures or fuels nearby, but the real world usually isn’t like that. Over several decades, I’ve been on a lot of fires in a lot of roles and aircraft types and environments, from single tree fires to large, complex fires that lasted for months. I’ve been present for crashes, significant singular loss of life on the ground and in flight and have experienced putting an airplane on a hillside during an active wildfire, myself. I’m familiar with the environment, but also very familiar with the public ignorance about wildland fire and air operations. That ignorance ranges from having watched Always to the former President of the United States suggesting that the solution is sending armies of firefighters into the field to clean the forest floors.

A good place to start is to pass the budget to give let wildland firefighters keep the temporary two-year wage they were offered two years ago (it’s about to expire), and then raise it. The real heroes of the fire operations put their boots in the ash on the fire’s edge, and they need the attention right now, before we suddenly lose a lot of undervalued and underpaid firefighters from the present ranks.

Before we cater to the easy solution, albeit one given in ignorance, of simply trying to put more aircraft over fires, it may be well to seek to understand the realities, rather than the hollywood mythology. In recent years, wild ideas have been floated that ranged from “aluminum clouds” of tankers, such that the sky is completely blanketed with air tankers dropping on fires all at once, to giant flying firestations made of balloons that pour waters on fires and douse them. Laughable and far from realistic, but easy, low-hanging fantasy fruit all the same.

Not nearly as sexy and not nearly as dramatic, but a good place to start, when it comes to wildfire preparedness, is to teach people (and convince them) to keep defensible space around their property. That accomplished, genuine progress will have been made.

It’s worth noting that one of the most efficient resources addressed by the Rand report, were single engine tankers. Go figure. It’s also worth noting that these represent the most numerous fixed wing tankers over fires today. Still, tools in the toolbox, and there is a need and a place for all the aircraft, from type III helicopters to VLAT (very large air tankers) to the plethora of overhead supervision such as air attack platforms, and those delivering personnel such as helicopters and smoke jump platforms.