History has an ANSWER for FAA’s 3rd party inspections

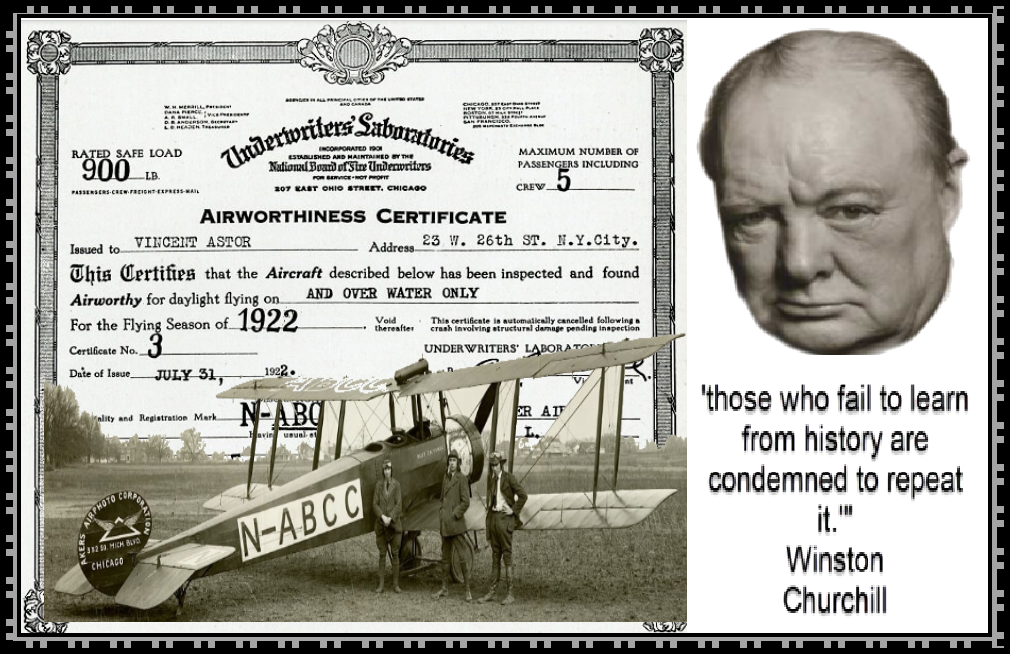

David Shepardson and Rajesh Kumar Singh, two highly regarded aviation journalists have authored a piece asking a timely question-Could a standalone non-profit be the answer to FAA oversight of Boeing? They then question a number of experts to opine on their provocative query. Though good comments were elicited, they failed to remember Mr. Churchill’s epigram. History, or more precisely history before the Civil Aeronautics Administration, Federal Aviation Agency, and the Federal Aviation Administration, the National Aircraft Underwriters Association sought help in determining what pilots and aircraft were coverable. Based on its recent experiences in analyzing the safety of automobiles, UNDERWRITERS LABORATORIES (UL) was designated as THE predicate for receiving insurance. [SEE 2ND ARTICLE BELOW.] While that assignment was a century ago and the volume was minimal, UL is a nonprofit[1] organization, and its current mission and competence are relevant to the challenges identified by recent examinations—

“Underwriters Laboratories (UL) is a global safety science company, the largest and oldest independent testing laboratory in the United States. Underwriters Laboratories tests the latest products and technologies for safety before they are marketed around the world. It tests 22 billion different products annually, ranging from consumer electronics, alarms and security equipment, to lasers, medical devices, and robotics…

Underwriters Laboratories is a non-profit organization funded by the fees it charges manufacturers of products submitted for certification. UL CHARGES FEES FOR THE INITIAL EVALUATION process, as well as ongoing maintenance fees for follow-up service. While UL is a profitable enterprise, that profit is filtered back into the business, as profit is not a stated goal of the company.”

Most significantly UL has tremendous technical resources, a known ability to assess risks of complex products’ safety and how to assign the best engineers to make these judgments. It INCLUDES UL RESEARCH INSTITUTES, a leading independent safety science organization with global reach. We sense and act on risks to public safety with bold hypotheses and objective investigations. Its size, its talented cadre of high-level engineers and financial strength offer a resource which can expeditiously assume inspections and quality oversight of Boeing and other type certifications.

Administrator Whitaker’s quote indicates that the function for setting AIRWORTHINESS STANDARDS would remain with the FAA; so, any fears of “PRIVATIZATION” would be irrelevant. Most importantly UL is recognized worldwide as THE STANDARD. It should also be noted that UL is able to recruit and retain an unequaled stable of engineers.

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM: the FAA does not charge for its certification services. One could argue that agency staffing is not adequate to respond, ON A TIMELY BASIS, to the strong demand from all aeronautical certification projects– new airplanes, eVTOLs, UASs, uncrewed aerial vehicles and maybe spacecraft. CFOs of the OEMs could cost out dollar impacts of the delays and the CMOs would be able to assign opportunity losses when foreign CAAs issue the TCs, PCs and ACs before their home certification.

Many of these requests include emerging technologies and innovative missions. Companies are sourcing parts, assemblies, and systems away from their headquarters and around the world. Materials are another arena of aerospace design that are testing the airworthiness determinations. Frequently these innovations require the existing workforce to be educated on these concepts rolling out of industry’s vibrant research.

THESE HIDDEN COSTS MAY JUSTIFY A FEE FOR THIRD PARTY OVERSIGHT AND INSPECTION.

Could a standalone non-profit be the answer to FAA oversight of Boeing?

February 8, 2024 3:34 PM

By David Shepardson and Rajesh Kumar Singh

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – The Federal Aviation Administration is exploring THE USE OF AN INDEPENDENT THIRD-PARTY TO OVERSEE BOEING INSPECTIONS AND QUALITY OVERSIGHT after evidence emerged the planemaker failed to install key bolts on a jet that suffered a midair emergency.

The question of oversight came into greater focus after the National Transportation Safety Board said on Tuesday it found evidence that suggested four bolts were missing on a door panel that blew out of a new Alaska Airlines 737 MAX 9 plane at 16,000 feet.

In the wake of the January accident, FAA ADMINISTRATOR MIKE WHITAKER has begun talking publicly about setting up A NON-PROFIT THIRD PARTY entity to potentially help oversee Boeing’s quality control.

Whitaker told Congress this week that an outside firm is reviewing a longstanding agency practice of delegating some aircraft certification tasks to Boeing. The FAA must certify new airplanes as safe before they can be delivered to airlines.

Senate Commerce committee chair Maria Cantwell, whose committee oversees aviation, said on Thursday she plans to call Whitaker for a hearing to discuss his idea in the coming months.

“The issue is how do you have the right technical people that really understand the technology and how do you get them in the FAA system, in the oversight system to be on the job now,” said Cantwell. Boeing’s 737 MAX planes are built in her home state of Washington.

In the U.S. House hearing Tuesday, Whitaker said the FAA “should look at a THIRD PARTY. I think it may be an option where there’s a higher level of confidence where we have more direct oversight ability, and where the folks doing certain critical inspections don’t have a paycheck that’s coming from the manufacturer.”

“I think what Whitaker’s looking for is an objective group,” said U.S. aviation safety expert John Cox, adding that it could work if the FAA were able to fund auditors, for example, to do such inspections.

The FAA, however, cannot afford to do the job on its own. In 2019, it told Congress it would need an ADDITIONAL 10,000 EMPLOYEES that would cost $1.8 billion annually if it were to assume all responsibilities for aircraft certification.

Arjun Garg, a former FAA chief counsel and acting deputy administrator, said the agency likely wouldn’t be speaking about the idea in public without having already given it thorough consideration.

He added that experts who specialize in aircraft engineering and manufacturing processes could perform that type of independent review, adding that entities such as the FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION OR EMBRY-RIDDLE AERONAUTICAL UNIVERSITY, which are well known and well regarded in aviation, could bring rigor and credibility to the task.

Problems with aircraft certification are not new. A December 2021 Senate report found “FAA’s certification process suffers from undue pressure on line engineers and production staff.”

In 2020, FAA employees reported fearing pressure from Boeing, with one employee saying: “It feels like we are showing up to a knife fight with Nerf weapons.”

Former House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee chair Peter DeFazio, who led a massive investigation into two earlier MAX crashes that killed 346 people, is skeptical of the third party idea.

“I know of no such entity ready to step in,” he said. If “we have a new independent entity supervising Boeing, then FAA would have to oversee the entity. I think it would be more straightforward to increase the FAA inspection workforce – which has never recovered from the cuts” made 30 years ago, he said.

(Reporting by David Shepardson and Rajesh Kumar Singh; Editing by Chris Sanders and Peter

Graff)

Taking flight: The early years of aviation

Like many breakthrough industries, the first few years of flight resembled the wild west more than a planned community. UL helped lay the foundation of aviation trust with THE FIRST U.S. REGISTRY OF PILOTS AND PLANES, PLUS AN “AIRWORTHINESS” CERTIFICATE PROGRAM.

February 15, 2019

Although Wilbur and Orville Wright made their first successful flights at Kitty Hawk in 1903, private and commercial aviation was slow to catch on in the early 20th century. It wasn’t until after World War I, when the Army had developed faster, safer and more sophisticated aircraft, that private and commercial flight truly took off in the United States. By 1921, it was estimated that there were 1,200 civil pilots in the U.S.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) did not exist yet, however, SO THERE WAS NO AGENCY TO REGULATE CIVIL FLIGHT. This caused a vast array of problems within the industry. Insurance companies were particularly affected because they had no method to underwrite the risks and hazards of flying.

In 1920, the National Aircraft Underwriters Association (NAUA) turned to Underwriters’ Laboratories for help, knowing that UL’s technical engineering expertise would be invaluable in addressing these issues. A few years earlier, UL had helped develop the methods for classifying automotive risks at the National Automobile Underwriters Conference. This gave UL the reputation as a leader in transportation safety.

In July of 1920, the NAUA officially adopted a resolution “to avail itself of the services of Underwriters’ Laboratories in connection with the inspection of planes and the establishment of adequate manufacturing standards.” Beginning in July of 1921, all members of the NAUA agreed that any aircraft they insured against fire, theft, collision, stranding and sinking had first to be REGISTERED BY UNDERWRITERS’ LABORATORIES.

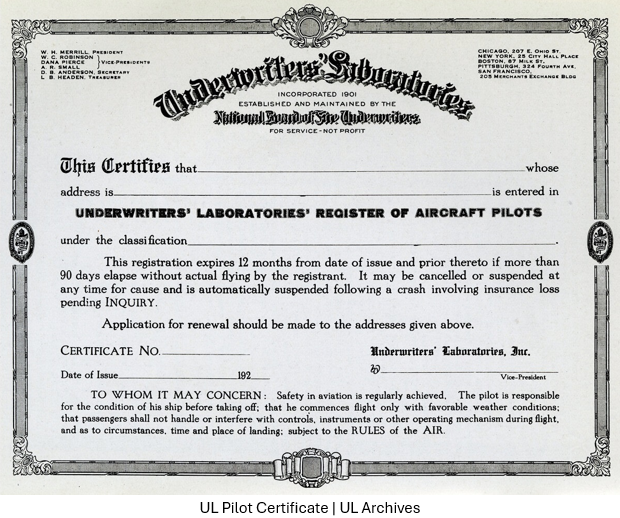

Ultimately, it was decided that UL would register both planes and pilots: after all, the safest pilot could not successfully fly an unsafe plane, and an unsafe pilot could not successfully fly a safe plane. The booklet RULES OF THE AIR, which UL published in August of 1921, was the first set of rules for civilian aircraft in the United States.

Getting started

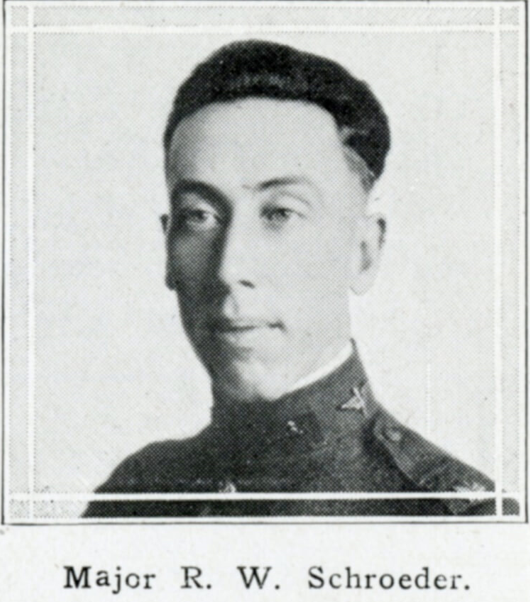

UL’s Aviation Department was officially in business by July 1, 1921. The first months were slow – although many individuals and organizations wrote in to say they were intrigued by the program, few pilots presented themselves and their planes for registration. Things began picking up in September, however, when Major R.W. “Shorty” Schroeder joined the staff.

In spite of the nickname “Shorty,” Schroeder was actually 6 feet 4 inches tall. He was said to be a “serious, sad-looking man who played a fine accordion.” | UL Archives

Schroeder was an experienced aviator – he built gliders from 1908-1910, worked as an airplane mechanic from 1910-1913, served overseas from 1917-1918 and eventually became the chief test pilot at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio. He had set multiple world records for the highest altitude achieved in flight between 1918 and 1920 and was no stranger to the dangers of flying. He was also extremely well-known throughout the aviation industry – many letters that delivered to UL’s Aviation Department came addressed simply to “Shorty.”

Schroeder quickly got to work, and between 1921 and 1925, UL’s Aviation Department registered 47 pilots. The goal of this work was to keep unqualified fliers out of the skies and to ensure that pilots were not being granted insurance if they could not be trusted to handle an aircraft safely.

Previously, insurance companies had typically required pilots to fill out a “pilot’s statement” before flying an insured plane. However, pilots were not always honest when reporting on their flight history. There was no way to verify their statements, which meant that “many pilots endeavored to take advantage of the fact by increasing the actual number of hours flown, omitting to report accidents and in other ways changing their records to make them acceptable for insurance.”

To receive a UL pilot’s registration, on the other hand, applicants had to provide a comprehensive flight history. This included: how many hours they had flown; whether they flew privately or commercially; where they had learned to fly; if they had flown in the war; if they had any kind of stunt flying experience; and if they had ever had any accidents. They also had to have a medical examination that proved their eyes, heart, lungs and other organs were in good working order. Finally, each applicant had to provide two references from people in the aviation industry. Schroeder would then write to each reference to make certain that the pilot in question was trustworthy, reliable and experienced.

If the pilot met all the criteria, they received a registration that expired after twelve months. The registration would immediately be suspended in the case of an accident or crash.

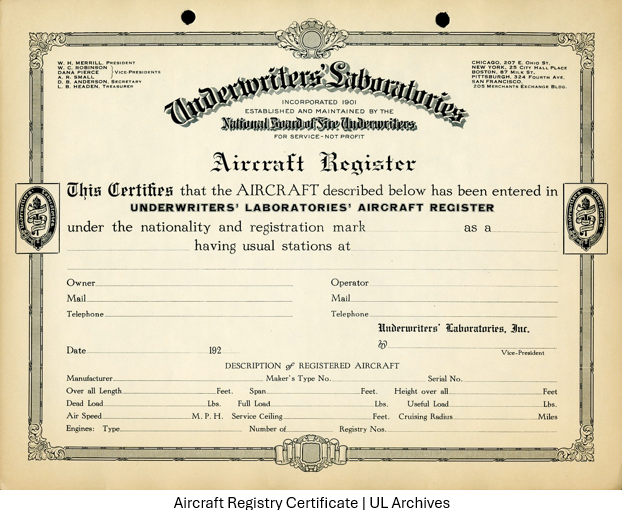

Aircraft registry

UL also registered 44 planes between 1921 and 1925. Each plane received a Certificate of Registry that covered the entire life of the plane, as well as a five-letter identification mark that was painted onto the plane. A plane whose mark began with “N” was owned by an American citizen and could be flown internationally. If the identification mark was underlined, it meant that the plane was intended for private use, rather than commercial.

Applicants for aircraft registration had to provide information about who owned the plane, who flew the plane and who had manufactured the plane. General specifications, such as the weight of the aircraft, the fuel capacity, the wingspan, the rated airspeed and the types of instrumentation were also noted. Finally, the applicant had to pay a $5 fee to receive a place on the registry, because the registration covered the plane’s entire life and didn’t have to be renewed every year.

Although no female pilots applied for a pilot’s registration, two female plane owners received UL registrations for their aircraft. Mrs. Tillie LaParle owned a Curtiss MF registered as N-ABCX, and Anna M. Parker owned a Curtiss JN-4D registered as N-ABKA.

The airworthiness certificate plan

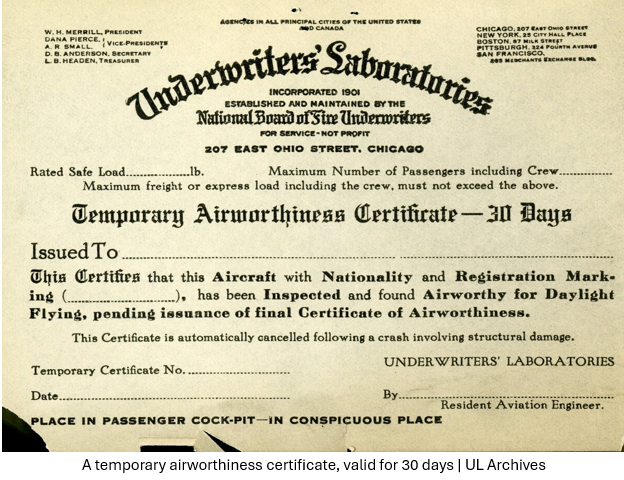

During the end of 1921 and the beginning of 1922, UL ALSO BEGAN CRAFTING AN “AIRWORTHINESS CERTIFICATE PLAN.” This would take matters a step further than simply registering pilots and planes, and actually delve into testing and certifying planes for safety.

For an aircraft to receive an airworthiness certificate, it had to be flown once a year and INSPECTED FOR MECHANICAL AND STRUCTURAL SOUNDNESS BY A UL AVIATION ENGINEER. Major Schroeder was based out of the Chicago office, so he hired on 33 other inspectors from all over the country to provide national coverage of UL’s services.

The airworthiness testing was rigorous: after a THOROUGH INSPECTION, the UL aviation engineer was required to fill out a 17-PAGE PACKET about the performance of various elements of the plane. Then the pilot had to take the aircraft up and fly it for the inspector, who was to remain on the ground (for his own safety). The pilot had to track his speed, oil pressure, water temperature and other factors while flying. IF THE PLANE MET ALL THE CRITERIA, A TEMPORARY AIRWORTHINESS CERTIFICATE WOULD BE ISSUED. AFTER THE REPORT WAS PROCESSED, THE OFFICIAL AIRWORTHINESS CERTIFICATE WOULD BE PRESENTED, VALID FOR 12 MONTHS.

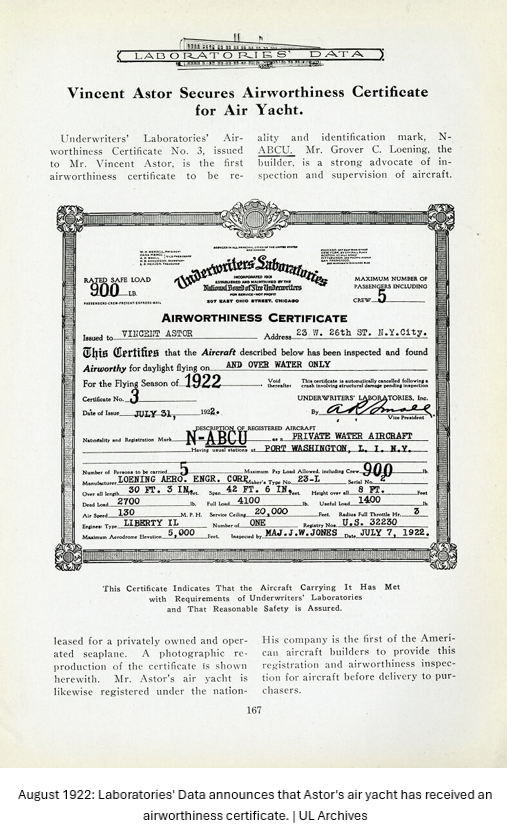

The airworthiness certificate program was not as successful as the pilot and aircraft registries – between 1922 and 1925, only 11 planes were certified for airworthiness. However, one of the most exciting episodes in the Aviation Department occurred because of the airworthiness program. In June of 1922, A.P. Loening of the Loening Aeronautical Engineering Company wrote to Major Schroeder to say that his company was building two planes and he wanted to have them added to the aircraft registry. He also wanted to have one of them certified for airworthiness.

This request was normal enough, but the future owners of the Loening aircrafts were not: socialites Vincent Astor and Harold S. Vanderbilt, two of the most famous Americans of their time.

G.C. Loening of the Loening Aeronautical Engineering Company designed two special versions of his Model 23 air yacht for Astor and Vanderbilt. Then Schroeder helped Loening register the two planes. He also contacted Major Junius W. Jones, UL’s resident aviation engineer in New York, to conduct airworthiness testing for Astor’s air yacht. Although Astor was the one to sign off on the paperwork, the air yacht was flown by a hired pilot, and not Astor himself.

Major Jones would later go on to become the air inspector of the Army Air Forces in 1943 and the air inspector of the U.S. Air Force in 1947. He inspected the aircraft, observed Astor’s pilot in flight and reported back to Schroeder on July 26th that the “airworthiness temporary certificate has been issued.” Astor received his final airworthiness certificate on July 31st, 1922, and UL received public recognition of the fact that aviation safety was important for everyone – whether the owner of a plane was a millionaire or just an everyday commercial pilot.

The end of the aviation department

UL’s Aviation Department lasted from 1921-1925 – just four brief years. By 1923, it was becoming clear that no matter how well-structured UL’s aviation program was, the U.S. government was going to need to manage the industry for it to reach its full potential. Airways and airports needed to be built, and there needed to be consistent, enforceable air traffic laws throughout the nation.

R.W. Schroeder moved to Detroit in April of 1925, taking on a new role with the Stout Metal Airplane Company at the Ford Air Post in Dearborn, Michigan. He worked in aviation for the rest of his life, eventually becoming the Vice President of Safety for United Air Lines.

In 1926, Congress passed the Federal Air Commerce Act, which charged the newly formed Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce with regulating U.S. aviation. The Aeronautics Branch would eventually grow into the FAA.

This doesn’t mean that UL’s early work in aviation was all for nothing, however. After all, UL pioneered the process of registering pilots and planes, put forth the first set of rules for the aviation industry and INSPECTED AND TESTED CIVIL PLANES FOR SAFETY BEFORE THE GOVERNMENT DID. The work of this department demonstrates UL’s lasting commitment to creating safe working and living environments for all people – whether on the ground or in the skies.

Sources

1 “An Analysis of Aircraft Accidents.” Aviation, September 26, 1921, 371-372

2 Summary of Underwriters’ Laboratories Aircraft Activities, 1958, Box 1, Folder 1, page 2, Water Damaged Collection, UL Archives, Northbrook, Illinois

3 “Underwriters Issue Pilot and Aircraft Registers.” Aviation, July 18, 1921, 78

4 “The Tall Legacy of ‘Shorty’ Rudolph William Schroeder.” Director of Maintenance, 2015. http://www.dommagazine.com/article/tall-legacy-%E2%80%9Cshorty%E2%80%9D-rudolph-william-schroeder-1885-1952

5 Ibid

6 Schroeder, R.W. “Adventures – With Earth Seven and One-Quarter Miles Below,” Laboratories’ Data, Chicago: March/April, May, June, July 1922, 62-65, 90-93, 130-133, 162-164. See also: Cooper, D.R. “Rudolph William Schroeder, 1886-1952.” (n.d.) http://www.earlyaviators.com/eschroed.htm ; “Aviation – Chicago Air Board Honors Schroeder,” Laboratories’ Data, Chicago, February 1922, 39

7 Martin, E.S. “Facts on Aircraft Insurance.” Aviation, January 2, 1922, 8-9

8 Letter from Major J. W. Jones to R.W. Schroeder, July 26, 1922. Water Damaged Collection, Airworthiness Certificates, Folder 4, UL Archives, Northbrook, IL

9 “Major R.W. Schroeder Resigns to Become Affiliated with the Ford Projects.” Laboratories’ Data, Vol. 6, No. 4, April 1925, 78. UL Archives

10 “The Tall Legacy of ‘Shorty’ Rudolph William Schroeder.” Director of Maintenance, 2015. http://www.dommagazine.com/article/tall-legacy-%E2%80%9Cshorty%E2%80%9D-rudolph-william-schroeder-1885-1952

[1] On January 1st, 2012, Underwriters Laboratories set up UL LLC as a For-Profit company in the United States. UL LLC has taken over Underwriter’s Laboratories product testing and certification business – undoubtedly the most profitable part of the Underwriters Laboratories business.