SWISS’s skin check valve case and its SRA

PEOPLE magazine identified (see below copy) that SWISS International Air Lines (Swiss) flew an A330 for six years with a pressurization system “skin check valve” that had been identified in a SERVICE BULLETIN, issued by the Toulese OEM, had RECOMMENDED –”earliest possible replacement of the skin check valve.”

The Swiss Transportation Safety Board (STSB)has now recommended that EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency) issue a mandatory Airworthiness Directive (AD) based on the Airbus bulletins for all A330 and A340 operators. Swiss has since initiated an accelerated replacement program for these valves across its long-haul fleet.

The legal status of an OEM Service Bulletin (SB) versus Airworthiness Directive (AD) is a distinction that is one of the most important in airworthiness law. NB SBs are not legally mandatory, in and of themselves; when a regulatory authority issues an AIRWORTHINESS DIRECTIVE, THEN the specified action is REQUIRED.

According to the PEOPLE magazine quotes, what appears to have been Swiss’ Safety Risk Assessment (SRA)(FAA version cited here), concluded that :

“had reviewed the matter addressed in the Service Bulletin concerning the check valve as part of the biennial inspection in accordance with the aircraft manufacturer’s maintenance program.”

“Where a defect was identified[1], the valve was replaced. Although the Service Bulletin recommends implementation, the assessment table contained therein indicates only an improvement in reliability. The Bulletin is not classified as a potential Airworthiness Directive,”

Here is a summary of the potential consequences of a failed skin-check safety valve (AI researched)

A safety consequences of failed skin‑check valve ,at cruise altitude on an A330, are very real because the valve sits in a part of the pressurization system that normally goes unnoticed—until it doesn’t. The skin‑check valve is a one‑way valve that prevents pressurized cabin air from leaking into the fuselage skin cavity and low‑pressure manifold. At cruise:

-

- Cabin pressure is equivalent to 6,000–8,000 ft

- Outside pressure is equivalent to 35,000–41,000 ft

- The pressure differential is huge, so any leak path becomes significant.

If the valve fails open, the cabin is no longer sealed as designed.

Immediate results of such a failure

-

- Immediately it is likely that a Slow or moderate depressurization

- Cabin altitude begins to creep upward

- Cabin Pressure Controllers (CPCs) try to compensate by closing the outflow valve

- Once the outflow valve is fully closed, the system has no more authority

- Cabin altitude continues to rise

This can take minutes to tens of minutes, depending on the size of the leak. But the crew may not notice immediately unless the cabin altitude trend is monitored closely. Which the Swiss crew did do!

Rapid depressurization (less common but possible)

If the valve fails catastrophically—e.g., hinge fracture, spring break, or sleeve rupture—air can escape fast enough to cause:

-

-

- Cabin altitude climbing rapidly

- Automatic oxygen mask deployment at ≈14,000 ft cabin altitude

- Immediate emergency descent required

-

This is rare but documented in investigations.

Physiological risks to passengers and crew

If the leak is slow:

-

-

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Mild hypoxia symptoms

- Crew may misattribute symptoms to fatigue or circadian disruption

-

If the leak is rapid:

- Hypoxia within seconds at FL350–390

-

- Oxygen masks deploy

- Unrestrained objects may shift due to pressure differential

- Temperature drops sharply in the cabin

-

Why this matters specifically on a transatlantic flight

Over the ocean:

-

-

- No immediate diversion airports

- No ATC radar coverage in parts of the NAT

- High traffic density on organized tracks

- Emergency descent may conflict with other aircraft on parallel tracks

- Crew fatigue is more likely on long‑haul flights, increasing detection risk

-

A depressurization event over the North Atlantic is one of the most complex emergencies a crew can face.

These are generic postulations of what might happen on a Transatlantic flight with a depressurized cabin; SWISS in doing its SRA had access to data and information directly relevant to its history of operations- a far more precise tool.

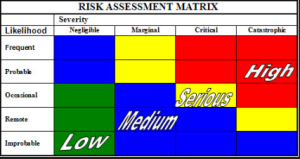

An SRA action may justify a decision. While the data used to decide in which of the 20 categories used for this tool, the objective numbers in this analytical algorithm need to subject to heavy scrutiny when the process is intended to prioritize SAFETY.

It is critical that the regimen designed for your company’s future such decisions is designed with the best practices in industry, An SME, who sees the SRAs of comparable organizations and is studious in being current on research in this device, is a valuable participant in the initial design and recurrent reviews.

Airline Slammed by Accident Investigators After 8-Year-Safety Warning Is Allegedly Ignored, Prompting Emergency Landing

Investigators called the airline’s lack of action “incomprehensible from a safety perspective”

By Marina Watts

SWISS International Air Lines is under scrutiny for an incident that happened in September 2024.

According to a report completed by the Swiss Transportation Safety Investigation Board (STSB), a faulty part in an Airbus A330 hadn’t been replaced in eight years, which triggered decompression, DESPITE SWISS INTERNATIONAL AIR LINES KNOWING ABOUT THE ISSUE FOR EIGHT YEARS.

In the final report, published on Jan. 19 and obtained by PEOPLE, an Airbus A330 left Zurich Airport for a transatlantic flight to New Jersey’s Newark Liberty International Airport.

Upon ascent, the pilots learned that there was an issue with the pressurization system, which allows everyone aboard the plane to breathe at high altitude. Even though the plane’s settings were adjusted appropriately, the defective “skin check valve” prevented proper pressurization.

Zürich International Airport.

“Although both outflow valves were indicated as fully closed, the cabin pressure system was unable to build up sufficient cabin differential pressure,” the report read.

“The cockpit crew donned their oxygen masks and initiated an emergency descent. They also manually activated the oxygen masks in the cabin for passengers and cabin crew and decided to return to Zurich, where the aircraft landed without incident.”

The Airbus, containing two pilots, 10 cabin crewmembers, and 205 passengers, descended 5,000 feet per minute before making an emergency landing at Zürich. The passengers and crew were able to exit the plane in a normal manner, and no one was injured.

Per the report, a “SERVICE BULLETIN PUBLISHED BY THE AIRCRAFT MANUFACTURER IN 2016 recommending the earliest possible replacement of the skin check valve with a modified skin check valve had not been implemented.” The skin check valve is meant to be inspected every 24 months according to the manufacturer, where it is removed, checked and reinstalled accordingly.

inspected every 24 months according to the manufacturer, where it is removed, checked and reinstalled accordingly.

The defective valve, which is meant to allow air into the cabin but was severely damaged and not replaced in eight years, allegedly caused the accident. The airline knew about the valve and cited costs as an issue for this maintenance, per the report.

“Past incidents and accidents have shown that it can sometimes be difficult for cockpit crews to detect such a slow pressure drop (subtle decompression), especially during the initial climb,” the report stated. “This can quickly lead to a dangerous situation.”

The report concluded that the skin check valve not being inspected or replaced led to the decompression and emergency landing.

Swiss International Air Lines plane.

Investigators called the airline’s lack of action to inspect the skin check valve “INCOMPREHENSIBLE FROM A SAFETY PERSPECTIVE.”

A spokesperson for Swiss International Airlines told PEOPLE in an email that the airline “had reviewed the matter addressed in the Service Bulletin concerning the check valve as part of the biennial inspection in accordance with the aircraft manufacturer’s maintenance program.”

“Where a defect was identified, the valve was replaced. Although the Service Bulletin recommends implementation, the assessment table contained therein indicates only an improvement in reliability. The Bulletin is not classified as a potential Airworthiness Directive,” their statement read.

“Against this background, we had decided that the regular inspection of the valve as part of the biennial check is sufficient. Implementation of such a Service Bulletin is not mandatory for maintaining airworthiness unless an explicit instruction is issued by the competent authority, for example, in the form of an Airworthiness Directive.”

“In the meantime, we had upgraded 12 of 14 aircraft to the new valve standard,” the statement concluded. “On two aircraft, implementation of the Service Bulletin is still pending; this is planned for the first quarter of 2026.”

[1] Presumably this aircraft was not inspected OR was inspected but the valve was determined to be airworthy OR the inspection failed to identify the valve that failed.???