Repetition supports Aviation Safety, but it also dulls Pilot’s focus- suggestions on how to assure continued attention

The Italian equivalent of the NTSB, ANSV, reported its analysis of a 2024 tail strike at Milan’s Malpensa Airport by a LATAM B-777. The below referenced report found that the PIC, in his routine entry of the aircraft’s gross take-off weight, miscalculated the correct numbers. The mistake was then transferred to the SIC’s EFB and thus the incorrect Vr speed resulted in the tail strike.

The most important on board flight computer is the pilots brain collectively. AI has to be carefully programmed to avoid certain biases. The human brain is highly influenced by its experience. Repetition is one of those cognitive experiences that affects future brain responses, in this case- decreasing its mental acuity.

The REPEATED PERFORMANCE of a task that is a prerequisite to every flight, the very routines that make flying safe,CAN, through repetition, DULL ATTENTION. Fortunately, human‑factors research[1] offers several evidence‑based techniques that HELP CREWS STAY COGNITIVELY “FRESH” while still following required procedures.

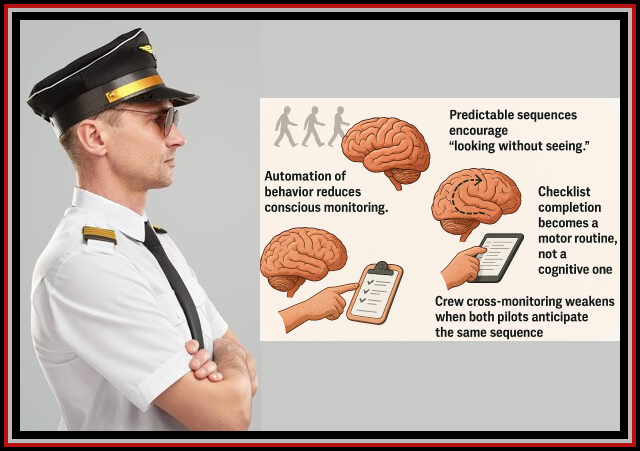

Human‑factors studies consistently show:

Human‑factors studies consistently show:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Automation of behavior reduces conscious monitoring.

- Predictable sequences encourage “looking without seeing.”

- Checklist completion becomes a motor routine, not a cognitive one.

- Crew cross‑monitoring weakens when both pilots anticipate the same sequence.

-

-

-

-

-

This is why modern checklist design emphasizes cognitive engagement, not just procedural compliance.

A summary[2] of those helpful techniques to counter the dulling of the flight crews’ focus includes:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Varying Checklist Order (With Limits)

- Randomizing or alternating order increases cognitive engagement.

- It forces the brain to re-evaluate each item rather than anticipate the next one.

- However, this is only appropriate for non‑time‑critical, non‑memory‑critical checklists (e.g., preflight, parking, securing).

- Do not vary order for emergency or abnormal checklists—those are optimized for flow and time.

- Varying Checklist Order (With Limits)

-

-

-

-

-

Airlines that use this technique:

Some Part 135 and Part 91K operators use “challenge order variation” for preflight or postflight checks to reduce complacency.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Role Reversal Across Legs

- This is widely supported in CRM research:

- Leg 1: Pilot A reads, Pilot B responds

- Leg 2: Pilot B reads, Pilot A responds

-

-

-

-

-

Benefits:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Prevents “one‑person mastery” and the other drifting into passive monitoring.

- Increases cross‑checking accuracy.

- Reduces “rote response” patterns.

- Variable Timing Between Items

- spacing items (2 seconds, 30 seconds, 5 seconds) aligns with:

- Interleaving theory (cognitive psychology)

- Spacing effect (Ebbinghaus, later aviation HF studies)

- Startle‑recovery research (NASA Ames)

-

-

-

-

-

Benefits:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Breaks the rhythm that leads to inattentive completion.

- Forces re‑engagement with each item.

- Helps detect “expectation bias” errors.

-

-

-

-

-

This is especially effective in walk‑around checklists or cockpit setup checks where items are tied to physical inspection.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- “Verification First” Technique

-

-

-

-

-

Instead of:

Reader: “Hydraulic Pumps?”

Responder: “On.”

Use:

Responder visually verifies first, then the item is called.

This is called “verify‑then‑call” and is supported by:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- FAA Human Factors Design Standard

- NASA ASRS studies on checklist errors

- ICAO Annex 6 guidance on checklist discipline

-

-

-

-

-

It reduces “call‑and‑response without looking.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Cognitive Forcing Functions

-

-

-

-

-

Borrowed from medicine and nuclear operations:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Insert intentional “thinking steps” before certain items.

Example: “Before checking fuel pumps, state the expected configuration.”

- Insert intentional “thinking steps” before certain items.

-

-

-

-

-

This combats confirmation bias and expectation errors.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Use of “Do‑Verify” vs. “Read‑Do” Modes

- Read‑Do is best for sequential, time‑critical tasks.

- Do‑Verify is better for tasks where situational awareness matters.

-

-

-

-

-

Switching modes based on context keeps the crew mentally engaged.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Introduce “Why” Statements Periodically

-

-

-

-

-

Not every flight, but occasionally:

“Checking anti‑ice because OAT is below 10°C and visible moisture is present.”

This technique is used in some European CRM programs to maintain situational relevance and prevent “checklist autopilot.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Micro‑Briefs Before Checklists

-

-

-

-

-

A 5–10 second “micro‑brief” before a checklist:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- “Let’s pay special attention to electrical items today; we had maintenance on that bus.”

-

-

-

-

-

This primes attention and reduces inattentive scanning.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Checklist Redesign Based on Human‑Factors Research

-

-

-

-

-

Studies show that:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Grouping items by system (not by cockpit location) improves comprehension.

- Limiting checklist length reduces attentional drift.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Using boldface or color cues for high‑risk items increases vigilance.

-

-

-

-

-

-

Not every airline may have a person with the cognitive expertise to translate these suggestions into explicit instructions that your cockpit crew will understand. It is equally important that your crews UNDERSTAND the NEED and VALUES of what they may regard as unnecessary psychobabble. Writing and communicating these two implementation keystones are available here.mailto:info@jdasolutions.aero.

100-Ton Weight Miscalculation By Pilots Caused LATAM Boeing 777 Accident In Milan

Credit: Shutterstock

Italian aviation authorities have concluded that a LATAM Airlines Boeing 777-300ER sustained a tail strike during departure from Milan Malpensa in July 2024 after a major take-off weight error. The aircraft was operating a scheduled flight to São Paulo when incorrect performance calculations led to an early rotation. Although the aircraft returned and landed without injuries, investigators later classified the event as an accident due to the extent of the damage. The findings point to a combination of human error and procedural failures rather than a technical malfunction.

The investigation, carried out by Italy’s National Agency for the Safety of Flight (ANSV) Agenzia Nazionale per la Sicurezza del Volo[3], provides a detailed reconstruction of how the miscalculation occurred and why it went undetected. The case has drawn attention within the aviation industry because it demonstrates how performance-planning mistakes can propagate through automated systems. Safety specialists say the incident underscores the importance of robust cross-checking and crew situational awareness. Lessons from the event are expected to inform future operational guidance and training.

Severe Weight Miscalculation Identified As Root Cause Of Tail Strike

Credit: Flickr

As reported by the Aviation Herald, according to the final report, the LATAM Boeing 777 departed Milan Malpensa Airport on July 9, 2024, with a gross take-off weight underestimated by roughly 22,000 lbs. (100,000 kg). The captain mistakenly deducted the expected taxi fuel when calculating the aircraft’s weight, resulting in a figure far below the actual value. That incorrect weight was then entered into the take-off performance tools used by both pilots. As a result, the aircraft’s calculated thrust settings and rotation speeds were invalid.

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9P8OBm-ot4]

Because the same erroneous data was used in both electronic flight bags, the standard cross-check process failed to expose the discrepancy. The aircraft’s flight-management system was unable to generate valid V-speeds and displayed a warning, but the crew did not fully appreciate its significance. The take-off was continued using speeds that were substantially lower than required, leading to the aircraft’s tail contacting the runway during rotation.

“The result, 228.8 TONNES instead of the correct 328.4 TONNES, was verbally announced and subsequently used by both pilots.”

Crew Cross-Checks And System Warnings Failed To Prevent Incident

Credit: Shutterstock

The Boeing 777-300ER was operating a long-haul flight to São Paulo with a high payload and fuel load, a configuration that leaves little margin for error in take-off performance planning. Because the aircraft’s take-off weight was underestimated by roughly 220,000 lbs (100,000 kg), the calculated V-speeds, including rotation speed, were significantly too low. Investigators found that the computed Vr was more than 30 knots below what was required for the aircraft’s actual mass, increasing the pitch rate during rotation and making a tail strike far more likely on departure from Milan’s Runway 35L.

After lift-off, the crew noticed abnormal indications consistent with an unusual take-off profile and possible aircraft damage. As a precaution, they halted the climb, coordinated with air traffic control, and elected to return to Milan Malpensa. To ensure a safe landing within structural limits, the aircraft jettisoned approximately 159,000lbs (72,000 kg) of fuel before conducting an uneventful approach and landing. While no injuries were reported among the passengers or crew, post-flight inspections revealed damage to the rear fuselage, tail skid assembly, drain mast, and surrounding structural elements.

The investigation also identified weaknesses in cockpit coordination and procedural compliance that allowed the error to go undetected. Critical weight figures were EXCHANGED VERBALLY RATHER THAN CROSS-CHECKED AGAINST THE OFFICIAL LOAD SHEET OR THE FLIGHT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM. Additionally, when the aircraft displayed a “V-speeds unavailable” message before departure, the crew did not fully assess its implications or consult applicable procedures. Investigators concluded that these lapses collectively undermined multiple safety barriers that should have prevented the take-off from continuing with incorrect performance data.

[1] FAA CAMI (Civil Aerospace Medical Institute); NASA Ames Human Factors Division; ICAO Human Factors Digests; Human Factors (HFES);Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine; Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making

[2] AI generated review of the information gleaned from the sited materials in fn1.

[3] “The ANSV is a public institution, with an autonomous decision making authority and it is settled as an independent body within the Civil Aviation System; therefore, the objectivity of its dealings is assured as requested by the EC directive 94/56/CE. To guarantee such independent position ANSV has been put under the surveillance of Presidency of the Council of Ministers. It is the only Civil Aviation institution which is not under the surveillance of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport.”

“The ANSV has two main tasks: a) to conduct technical investigations for Civil Aviation aircraft accidents and incidents and to issue safety recommendations as appropriate (with the exclusion of accidents and incidents to State Aircraft); b) to conduct studies and surveys aimed at increasing flight safety.”