CONTINUOUS AVIATION SAFETY IMPROVEMENT must look at the details-even the color of the Passenger emergency cards text

Passengers – as defined by ages, nationalities, familiarity with travel, mobilities and other human attributes—change over time. Aircrafts – emergency systems, seating, evacuation equipment and routes- have new designs. Safety Research, in particular, has seen dramatic insights even over the past decade. Passenger safety cards, 1st issued a century ago, appear to be essentially the same as the last decade. All aspects of AVIATION SAFETY are impacted by these changes. Below is an interesting article about a small company located in Lacey, Thurston County, The Interaction Group, its founding, its 600+ customers and its evolution from its first distribution of the cards that fit in the back of the seat in front of the passengers through its evolution of messages, text, images, even colors.

Here is a summary of what The Interaction Group sees as the best way to communicate each airline’s passenger emergency protocol—

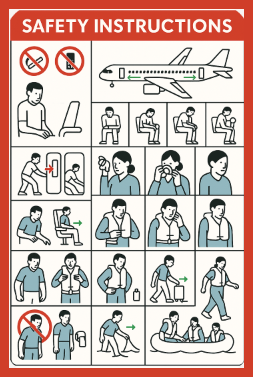

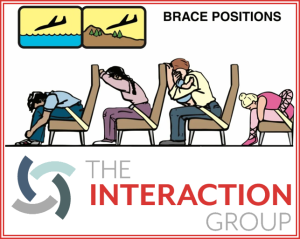

- Visual Design: What Makes “Best‑in‑Class” Images

Research and industry testing emphasize that images—not text—carry the primary safety load on modern cards. Key findings include:

Characteristics of the most effective images

- Highly simplified, schematic illustrations rather than photorealistic art. These reduce cognitive load and avoid cultural misinterpretation.

- Consistent iconography across the entire card (line weight, color palette, character style).

- Clear figure–ground separation (high contrast, minimal background clutter).

- Sequential, left‑to‑right or top‑to‑bottom action frames that mirror natural reading patterns.

- Depictions of human figures with neutral or culturally non‑specific features, which improves global comprehension.

- Color used sparingly—typically to highlight hazards (red), required actions (green), or equipment (yellow).

- Avoidance of ambiguous perspective; orthographic or slightly isometric views outperform dramatic angles.

Why these work

Human‑factors testing shows that passengers under stress rely on rapid visual recognition, not reading. Cards that minimize decorative detail and maximize symbolic clarity produce faster and more accurate interpretation.

- Message Clarity and Information Architecture

Safety‑card comprehension depends as much on layout as on the images themselves.

Effective clarity strategies

- Chunking information into discrete modules (e.g., brace position, exits, flotation, oxygen masks).

- Consistent panel structure across aircraft types within the same airline to reduce passenger confusion.

- Use of universal hazard symbols (e.g., no smoking, no luggage during evacuation).

- Avoiding text redundancy—too much text reduces attention to critical images.

- Testing with real passengers in timed comprehension trials, a practice emphasized by major safety‑card design firms.

Common clarity failures

- Overly dense cards with too many panels.

- Mixed artistic styles (e.g., combining cartoons with technical diagrams).

- Ambiguous arrows or unclear sequencing.

- Depictions of unrealistic passenger behavior (e.g., smiling during evacuation), which reduces perceived seriousness.

- Readability and Cross‑Language Comprehension

Because many passengers do not speak the airline’s primary language, research consistently shows that text‑light, image‑heavy cards outperform text‑heavy cards.

Key findings

- Pictograms outperform multilingual text blocks for nearly all safety actions.

- Culturally neutral characters reduce misinterpretation among passengers unfamiliar with Western gestures or norms.

- Minimal reliance on written instructions is recommended; when text is used, it should be extremely short and placed adjacent to the relevant image.

- Passengers with limited literacy or non‑Roman alphabets show significantly higher comprehension when cards rely on standardized aviation symbols.

- Color‑coding (e.g., green = do, red = don’t) improves comprehension across language groups.

The story below supports these general recommendations with examples in the course of the company’s research and development. The message for all airlines should be old, reliable charts, instructions, drawing, use of language…likely require revision. Aviation Safety, in all its dimensions, IS NOT STATIC!!! Continuous improvement cannot overlook details, like use of a RED X or the form of the people showing safety steps in an event of an accident.

The simple message-that passengers MUST NOT disembark in an emergency, though graphically [and orally] explained—has not been as effective as needs be:

SAFO “emergency evacuations pax and bags” will lead useful, practical approaches

Self-examination is not advised. What has worked in the past is known as STATUS QUO BIAS and by definition requires an independent view to detect. Other behavioral phenomena– UNCONSCIOUS INCOMPETENCE, KNOWLEDGE BLINDNESS AND INFORMATION DEFICIT BIAS—all mitigate in favor of bring a resource well-versed in current safety research, awareness of other practices and real time knowledge of what the ASAP data is flagging.

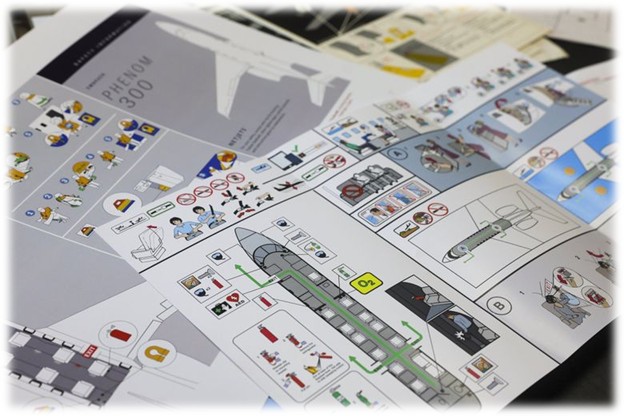

How seat-back psychology helped a WA business build a dynasty

Archival airplane safety cards at The Interaction Group in Lacey, Thurston County. The Interaction Group prints about 16 million safety cards every year. Since its founding in 1971, the company has worked with over 600… (Kevin Clark / The Seattle Times)

Lauren Rosenblatt Seattle Times business reporter

LACEY, Thurston County — In an unassuming office park a 90-minute drive south of Seattle, one company is churning out dozens of the TRIFOLD SAFETY CARDS travelers find tucked into their seat back pocket after boarding a flight.

There’s a good chance you’ve seen one. prints about 16 million safety cards every year. Since its founding in 1971, the company has worked with over 600 airlines on 18,000 projects.

CEO Trisha Ferguson credits The Interaction Group’s founders with researching, designing and printing the first illustrated safety card, ushering in a switch from text-heavy pamphlets to hand-drawn illustrations meant to help passengers in an emergency.

“We have 55 years of aviation illustrations and safety equipment, and instructions, so we are not often starting from scratch,” Ferguson said. “However, there is always something new in aviation.” (Kevin Clark / The Seattle Times)

The idea came from two psychologists who worked at what was then Douglas Aircraft, before it merged with McDonnell Aircraft Corp. and ultimately with Boeing. After researching aviation accidents, the PSYCHOLOGISTS recommended airlines give passengers easier-to-understand instructions about how to evacuate the plane.

More than 50 years later, illustrated safety cards are ubiquitous, and regulators require airlines to fly with safety cards unique to each aircraft.

Archival panels of early airplane safety cards at The Interaction Group in Lacey. Designing safety cards can be tedious work — sometimes designers at The Interaction Group have to test details as small as whether a hand should be moved just 30 degrees to the left for better comprehension, Ferguson said. (Kevin Clark / The Seattle Times)

Archival panels of early airplane safety cards at The Interaction Group in Lacey. Designing safety cards can be tedious work — sometimes designers at The Interaction Group have to test details as small as… (Kevin Clark / The Seattle Times

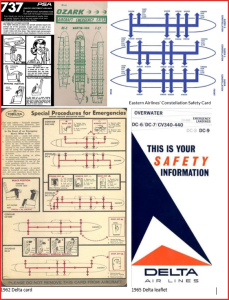

The Interaction Group has seen the switch from hand-drawn illustrations to digital designs, from sketches featuring passengers in suits and skirts to hoodies and sweatpants, from practically all-white figures to a diverse cast of characters, following research that readers are more likely to pay attention to content that looks like themselves.

Designing safety cards can be tedious work — sometimes designers at The Interaction Group have to test details as small as whether a hand should be moved just 30 degrees to the left for better comprehension, Ferguson said.

The cards change to reflect new safety guidelines and LESSONS ABOUT HOW READERS INTERPRET INFORMATION. In the ’80s, for example, The Interaction Group LEARNED READERS ASSOCIATE A RED X WITH A TREASURE MAP and thought the symbol was marking THE SPOT instead of indicating something passengers should not do. The company switched to a circle with a long slash through the middle.

“Every single little piece of these has intention and has science behind it,” Ferguson, 49, said during a recent visit to the company’s Lacey headquarters. “Feedback is the breakfast of champions around here.”

A shift in the industry

Safety cards — pamphlets describing what to do in case of an emergency — began appearing more than 100 years ago, according to Fons Schaefers, a safety card collector and amateur historian based in the Netherlands.

History and Development of Airline Cabin Safety

He found a 1924 “safety leaflet” from KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, which he believes is among the first iterations of the safety card. Many major airlines, like Pan Am, started making and distributing their own cards after World War II. Those were more like “small books,” Schaefers said, with some stretching to 24 pages.

He found a 1924 “safety leaflet” from KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, which he believes is among the first iterations of the safety card. Many major airlines, like Pan Am, started making and distributing their own cards after World War II. Those were more like “small books,” Schaefers said, with some stretching to 24 pages.

In the 1960s, the Federal Aviation Administration mandated safety cards,[below images] hoping to reduce the number of deaths from aircraft accidents.

Around the same time, psychologists Daniel Johnson and Beau Altman were researching why aircraft fatalities were not decreasing, even as planes were getting safer. Working for Douglas Aircraft, the pair found that even when passengers survived the impact of the crash, they often were UNABLE TO SAFELY EXIT THE PLANE. They recommended a PICTURE-FOCUSED SAFETY CARD TO REPLACE THE TEXT-HEAVY PAMPHLETS.

Airlines liked the idea and asked for help executing it, according to Ferguson.

So, Johnson and Altman formed what was then called Interaction Research Corp., working from their garage in Long Beach, Calif. It took three years to design and illustrate the first safety card.

The company moved to Olympia in the 1980s to be closer to Boeing.

Today, there are few companies that make aviation safety cards. Asked about major players, Schaefers pointed to two Washington-based firms founded by former Interaction Group employees, and another competitor that may now be defunct. Several airlines still make their own cards, he added.

After years of researching safety cards and cabin safety, Schaefers worries the pamphlets aren’t as effective as airlines and regulators want them to be. The cards today are cluttered, he said, filled with so many symbols that it’s difficult to pick out the most important details.